Full Circle - Loving Our National Forest Trails

How You Can Help

Trails like these don’t fix themselves. They require:

✅ Skilled professionals who pour hours of work into every foot of trail.

✅ Volunteers like you who show up, tools in hand.

✅ Donors who believe trails are worth investing in.

This is your chance to make an impact.

Donate Now to help fund this critical project and ensure Shenandoah’s trails remain wild, rideable, and sustainable—for the next generation of riders, hikers, trail runners, builders, and dreamers.

Hey 👋 It’s Kyle I’ve got a personal connection to our latest National Forest project:

It was my second ride ever on trails in the Shenandoah Valley. Rim brakes. A suspension fork that didn’t move, new to me clipless pedals, and the biggest climb of my life. It was early September 2003, and I was pedaling up the pavement on 257 with no idea that Reddish Knob could be so far away and would take so long to reach.

At the top, Thomas Jenkins pointed out all the surrounding mountains, told me some of their names, and blew my mind. I learned about an upcoming 100-mile mountain bike race held on those mountains in the coming days. This blew my mind for a few reasons:

- I had no idea people rode their mountain bikes 100 miles.

- I couldn’t believe there were enough trails and space to ride 100 miles on a mountain bike.

- I was out of food and water and exhausted from pedaling for what felt like hours on end.

It was my second Friday “Six Pack Downhill” ride with community folks, and I didn’t know what to expect. We started down the trail (Timber Ridge) off the top of Reddish. I walked the top part, the steps, the rock garden, and some steep sections.

My hands burned, and I was terrified. I thought my bike would break, and I was afraid I couldn’t come to a stop. We rode Timber Ridge trail to Upper Wolf Ridge to Lynn trails, and at the bottom, I was glad to make it down in one piece. The long descent on Timber, Wolf, and Lynn trails felt remote, wild, exhilarating, and somehow special.

The next day, I returned in a pickup truck, “Big Red,” with a friend and driven by Thomas Jenkins for Saturday volunteer trail work. I had no idea what to expect but was eager to help. A community ethos was that you ride the trails and care for them. After all, I felt like I had ridden my bike the day prior in the middle of nowhere, and if we didn’t help, who would?

We stopped and pulled up to a parked car as we passed the Briery Branch Reservoir. A kid and his mom got out and unloaded his bike. Thomas seemed to be expecting them, so we loaded the bike in our car. The kid climbed into the truck with us and then waved goodbye to his mom.

I was amazed; this kid must have only been ten years old, and he brought his bike. We drove further, turned onto a dirt road, bumped along, crossed a creek, and finally parked near a gate marked “Private Property.” Then, the hike began. It was steep. It felt like the steepest hike I had ever been on, probably because of the heavy trail work tools in my hands.

It felt like we hiked for over an hour (I now know we walked less than a mile). Finally, we reached our work site, unloaded the tools, and got to work. I had some trail work experience from volunteering with MORE up in Northern Virginia, but this was different. We were trying to build a rolling grade dip (think big drain) from scratch on a really steep trail. At each pause, it always seemed like Thomas wanted the drain to be longer and deeper, so we kept digging.

After what felt like forever, we started to pack up, and Thomas asked the kid (who had pushed his bike up the trail with us) to “speed check” our work by riding down it. Mind you, this was the same trail I white knuckle descended the prior evening. This kid floated along, jumped off our drain with a smile, and continued down the trail, looking very much like he knew exactly what he was doing.

I’m not sure how much “work” that kid dropped off by his mom did that day, but what an experience for a ten-year-old! What an experience I had pairing an evening ride with volunteerism on the same trail, all within a 24-hour window. Little did I know that I would see that kid a whole more.

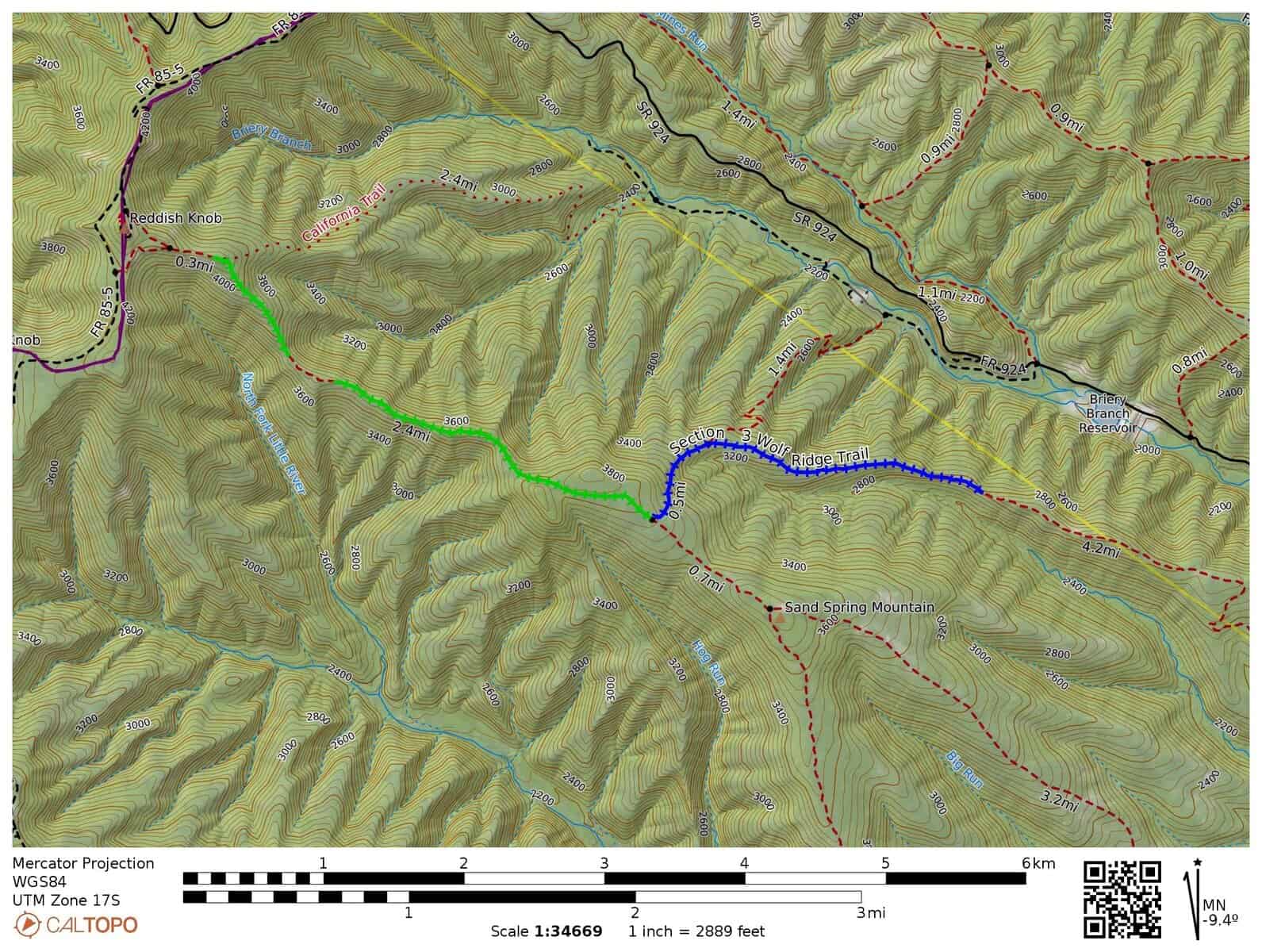

It’s November 14, 2024, twenty-one years later. I’m hiking up the same trail (Lynn), this time alone. It starts to snow, and the wind is blowing out of the west. I’m just a few years older and have been involved with the trail community for two decades. I’m headed up to check on a big trail improvement project on Timber and Wolf Ridge Trails.

I make it past the site where we built two (I hope we built two) rolling grade dips over twenty years ago on my first National Forest Trail work day. I reach the Wolf Ridge Trail and continue up towards Timber Ridge. Right as it gets super steep, I meet that kid again, the one from twenty years ago. Only this time, he’s a little bit older. He doesn’t have a bike and is perched on the side of Shenandoah Mountain in an excavator, moving rocks into places far too large to ever move without serious mechanical advantage.

That “boy” has grown up. He’s now a skilled machine operator who is able and willing to work on remote trails alone in an excavator on the side of a mountain. He has started his own business and builds and maintains trails for a living.

Twenty-plus years later, I’m still working on the same trail with that same kid. This time, we’re accomplishing a whole lot more. This time, we’ve grown and cultivated a much bigger community of people who care about these trails. Now, I work with partners to help fund projects where professionals like Sam Skidmore can spend full working days improving our backcountry trails for everyone.

I am in awe of the amount of work that has gone into the steepest and most eroded section of the Wolf Ridge Trail as it drops off of Timber Ridge. The result of a few days’ work with the machine could have easily taken volunteer crews hundreds of hours to complete with a very long and arduous hike into the location. The volume of work and scope of improvements are mindblowing.

The improvements are incredible: tread reconstruction, copious rolling grade dips (drains), and gorgeous sustaining rock armoring to protect the steepest sections of the trail from erosion and use.

Similar work was already completed nearly up to Reddish Knob on the Timber Ridge Trail, with work kicking off in early October.

That “kid” has been working many full days alone in the woods to improve our public lands, one drain, one armored rock section, and one foot of rebuilt trail at a time.

That kid is Sam Skidmore, owner of Rugged Trails (a local professional trail contractor). The work is done in conjunction with another great company, Greenstone Trail Craft (Andrew from Greenstone built the Upper Dowells Draft/ Magic Moss trails for us nearly ten years ago).

I am amazed at what we can accomplish with machine work on our trails—especially the range of maintenance improvements we can tackle with full-time contractors running excavators and other equipment. I still love connecting people to our public lands through volunteerism, but I now better recognize where and how to prioritize that time.

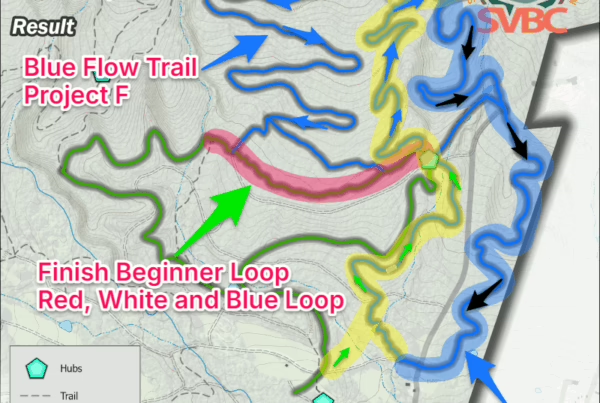

But it doesn’t happen by itself. This project was made possible thanks to the Appalachian Conservation Corps, a youth trail corps located in the Shenandoah Valley. In partnership with the Coalition, they secured a federal grant to cover the maintenance work on these trails and pay for their crews to maintain many other trails on Shenandoah Mountain, like Mines Run, the Shenandoah Mountain Trail, Hone Quarry Ridge, and Big Hollow.

We’re (The Bicycle Coalition) responsible for the 20 percent match for this project, which comes out to about $16,000. We were able to log over $6,000 from in-kind volunteer hours on these trails, but we need your help to close the gap. We hope to raise an additional $10,000 to cover our match for this project.

Can you help? Do you know someone who would like to help?

This full-circle story of community connectivity sure feels like Shenandoah Pixie Dust to me. There is something magic about the collection of people who care for our trails, who volunteer to support them, who donate to help them, and who run the machines to do the volumes of work required to keep our public lands accessible and environmentally sustainable.

I can’t believe my luck to work on the same trail twenty years later with the same guy his mom dropped off to help when he was ten years old. Even better, that guy has turned into a force for good in our trails community—someone who cares deeply about his work and about making our public lands better for everyone.

One Comment